Crime Novel Catch-Up #2: Before You Knew My Name

On an award-winning novel from 2022 I am only now getting around to reading

Dear TCL Readers:

First, a few housekeeping notes: I meant to post this newsletter last week about a different, older book, but the Bay Area trip for the UC Berkeley Law School event ate up all my time, and much as I’d like to keep to a weekly schedule, realism ought to win the day for a while.

I was interviewed by Katherine Igoe for the paper’s “Times Insider” column about, essentially, my life in crime — how it started, how it’s going, where crime fiction and true crime overlap, and how “reading crime fiction is a way to reconnect with all aspects of myself.” It was a pleasure to speak with Katherine for the piece, which also appeared in Tuesday’s print edition (A2), and enjoyed Anson Chan’s accompanying artwork (pictured above.)

The interview’s timing is fortuitous as I’m giving a talk tonight at 7 PM at the Darien Public Library on the various facets of my career — details and RSVP here. After that, I’m done with my own events for a while, though I’ll be in conversation with various writer friends, and will post details when I have them.

What I will be stumping for regularly has nothing to do with work: my choir, Cecilia Chorus of New York, has its winter concert at Carnegie Hall on Saturday, December 16 at 8 PM. It’s shaping up to be a one-of-a-kind concert, as we’re premiering a new work, Everyone Everywhere by Daron Hagen, commissioned by the Chorus for the 75th Anniversary of the UN Declaration of Human Rights — a document that feels more relevant and urgent than ever. We’re also singing Vaughan Williams’ Dona Nobis Pacem, set to biblical texts and Walt Whitman poetry. Ticket information is here, and I would be thrilled for any newsletter subscribers to attend.

Now, to the crime novel catch-up:

**

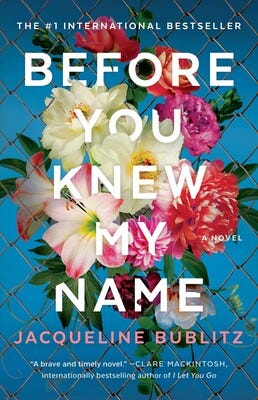

Here was another debut novel that I had a hard time finding, despite its award-winning status — garnering both the Best Novel and Best Debut Ngaio Marsh Awards, various crime prizes in Australia, and the Barry Award — and a glowing notice last year by Flynn Berry for the New York Times Book Review. So when I did, I tore into it immediately, and finished feeling rather odd about the whole thing.

On the one hand, I found Bublitz’s writing style quite inviting, one that is infused with warmth and empathy for how much her characters long for connection — whether they are among the living or dead. And I wasn’t put off by the narrator, midwestern transplant Alice Lee, whom we quickly learn has been raped and murdered in Riverside Park but who rages that the world won’t let her be seen as anything other than a pretty young white unidentified woman ripe for the true crime industrial complex mill.

“When the dead speak back,” declares Alice, “we are seldom loud enough to be heard over the clamor of all that living going on.” Getting around the “clamor” of life spurs Alice to, she hopes, send some kind of subliminal message to the woman who discovered her body — Ruby Jones, twice Alice’s age, recently arrived from Australia, lonely beyond belief, seeking meaning and even salvation in discerning the girl’s true identity and her killer.

On the other hand, Before You Knew My Name is full of narrative choices that only make sense if you know a little bit about Bublitz’s biography, and fall apart without those connections. Alice is from the Midwest because Bublitz spent time in Michigan as a teen. Alice goes to New York (and dies there) because Bublitz visited New York for a few months around 2014, and figured out that Riverside Park would be a good place to dump a corpse. Ruby is Australian because Bublitz, a New Zealander, lived in Melbourne for many years before returning to her hometown.

But I never felt like Bublitz made a compelling case for why the novel had to be set in New York City, or why Alice was originally from the Midwest. Neither setting felt particularly memorable — I kept wondering what bodega did she go to, which stores did she window-shop at, whether she would have crashed someone’s house party or gone to a show or attempted to get into some club, and how she felt about the vermin or the piles of trash accumulating in the streets.

Considering the impoverished, orphaned life Alice was running away from, it’s more wish fulfillment that the apartment ad she answers is from a kindly older gentleman, and that she would be cut break after break without much struggle. (Are eighteen-year-olds going to end up in beautifully kept Upper West Side apartments, rather than some rat-infested, insanely expensive hole-in-the-wall room in a less desirable neighborhood? Exactly.) Perhaps the point was to illustrate that such a fantasy life would be undercut by the cruel randomness of her violent death, but shouldn’t Alice’s life matter regardless?

Ruby, in her aching loneliness, was a more convincing character, because she’s set up deliberately as an outsider barely able to navigate the world she’s arrived in. She has a married lover she can’t quite shake off, and a sense of disconnection from the city she’s supposed to love. It takes a mystery — the identity of the girl we know as Alice Lee — to shake off Ruby’s drifting and to propel her towards others also desperate for connection, united in grief and loss, but also resolve.

I should also point out that Alice as narrator is hardly novel — another Alice, Sebold, made such a device famous with her 2002 international bestseller The Lovely Bones, a book I can’t bring myself to revisit after everything that happened with Lucky. Which, alas, brings me to another key issue of Before You Knew My Name, which is that critiquing the “Missing White Woman” idea cannot compensate for the inherent whiteness of this novel, particularly when it’s set in Manhattan. Even a few sentences where Alice, or Ruby, truly notice the world they inhabit, and how their choices — even the worst ones — would never be available to those in more marginalized groups, would have improved the book.

Yet I’m glad I read Before You Knew My Name, and engaged with what Bublitz set out to do. Her project is one I understand and support, even if I found fault with its execution. I suspect commercial fiction that has less to do with crime and more to do with human connection is going to be Bublitz’s forte going forward.

Until next time, I remain,

The Crime Lady